The Farjam Collection is one of the most

impressive privately-owned collections in the world today. Featuring

Islamic and pre-Islamic art, Contemporary Middle-Eastern art and

International Modern and Contemporary Art, the Collection is born of a

passion for art, exploration and travel, reflecting the affinities and

tastes of a seasoned collector. Through a timeless journey into art, it

embodies the fusion of cultures and traditions between East and West.

The Islamic section of the collection spans the entire history of

Islam, bringing together items produced throughout the vast region

between Andalusia and Mughal India. Its treasures include Quranic

manuscripts, miniatures and illustrated books on science, mathematics

and poetry, as well as finely-decorated metalwork, lacquer, glasswork,

tiles, glazed pottery, woodwork, textiles, coins, jewelry, and fine

carpets.

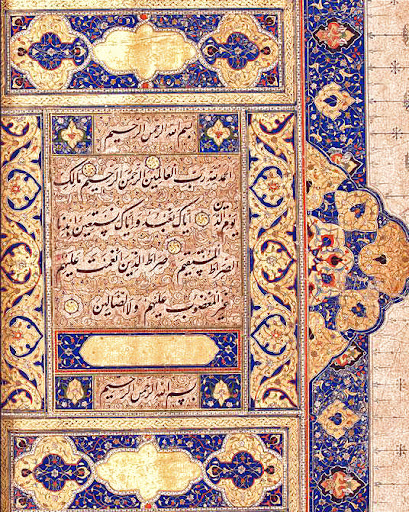

The Holy Quran

|

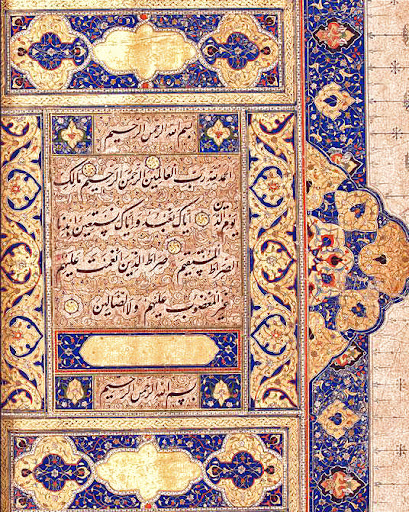

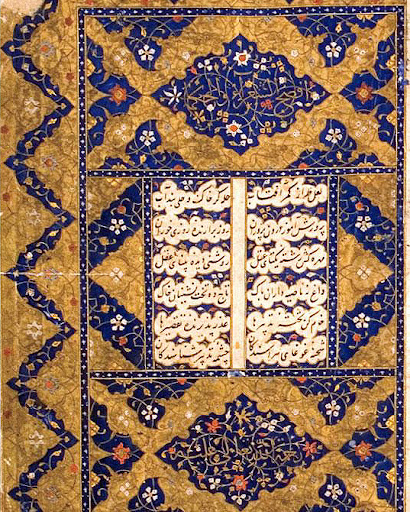

| An Illuminated Quran. Iran. Circa 1540 – 1550 AD / 947 – 957 AH. Signed Mir Hussein Al-Sahavi Al-Tabrizi | . |

|

| |

Qur’anic manuscripts and calligraphic forms

with which the word of God was recorded were of great importance. As a

means to express praise, faith and adhesion to Islam, transcriptions of

the Qur’an were highly valued. Over the centuries, a variety of scripts

were used, including Hijazi, Kufic, Thuluth, Muhaqqaq. Nakshi and

Rihani. Each followed strict rules of design put forth by master

calligraphers as early as she the 4th century AH. Decorated with

elegance, care and sincerity, each Leaf reflects the scribe’s mastery of

proportionality and the efforts of a number of other specialists from

paper makers to bookbinders.

|

| An Illuminated Quran, Iran. Dated 734 AH / 1333 -1334 AD. |

Particular attention was given to the illumination of Qur’anic

manuscripts and these now document the evolution of illumination as an

Islamic art. The decorations, initially limited to gold illuminations

and simple heading illustrations, readied their highest levels of

sophistication between the 7th and 11th centuries. The Holy Quran.

|

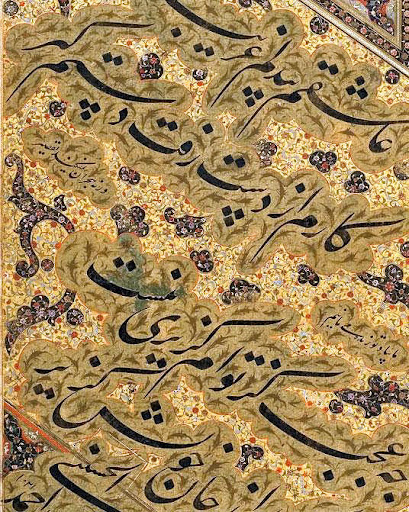

| An Illuminated Quran (detail). Iran. Dated 1243 AH / 1827 AD. |

The Manuscripts

|

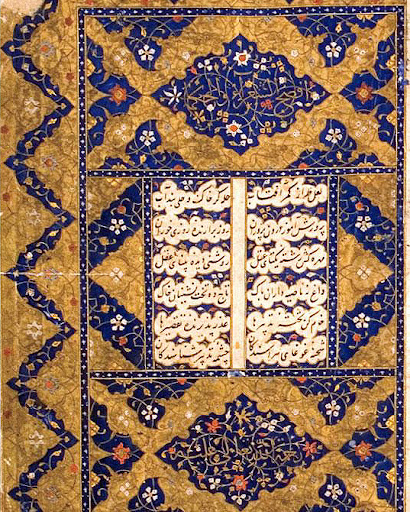

| Nizam Ganjavi's Khamsa. Iran. Dated 875 AH / 1471 AD. |

While early secular manuscripts from the

Islamic world were simple and unadorned, they became increasingly

stylized and ornate as the techniques employed in Qur’ans were gradually

applied to a wider variety of texts. During the 6th and 7th centuries,

as Baghdad became an important cultural centre, numerous scholars

participated in the production of Scientific and literary words on

subjects such as mathematics, a sinology, medicine, history, and poetry.

From the 7th century onwards, such texts were accompanied by detailed

paintings and images. These complemented the art of calligraphy and

added a new visual dimension to the manuscripts, different from

traditional Qur’anic illumination.

Secular books and manuscripts were treated with such skill and

technique that some examples are considered not only as valuable

documents, but also as artworks in their own right. The striking

delicacy of later pieces made manuscript illustration one of the most

lauded forms of Islamic art and helped disseminate the culture and

religion of Islam throughout the world.

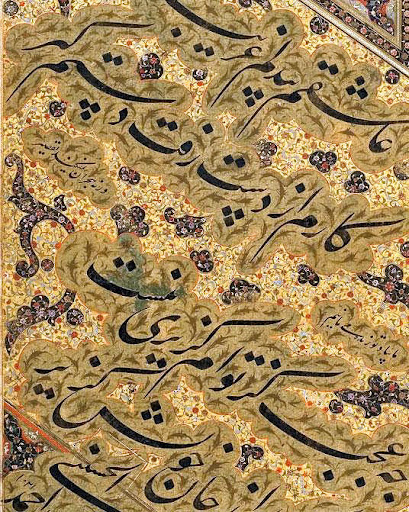

Calligraphy

|

| A Calligraphic Panel in Nastaliq Script. Iran. Dated 1021 AH / 1612 AD. Signed Ahmad Al-Hosseini |

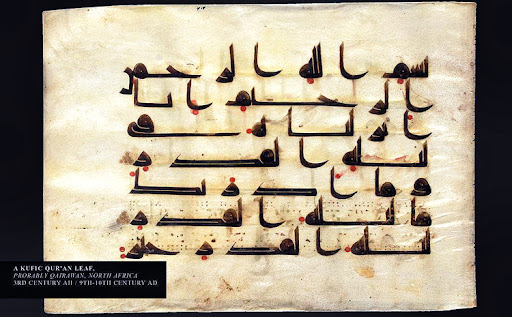

Originally used to transcribe the heavenly word of the Qur’an,

Islamic calligraphy was from its inception associated with sacredness

and spirituality. Early Hijazi and Kufic scripts were adopted to

transcribe the Qur’an, gradually evolving into more complex and stylized

forms that could be adapted to different media and subject matters.

Classical scripts were perfected during the 4th century AH by Vizier Ibn

Muqla who also classified the six most popular styles of writing or

Aqlam-i- Silta, known us Muhaqqaq. Rihani, Thuluth, Naskhi. Taqi and

Riqa. Furthering the achievements of these early treatises, prominent

masters such as Yaqut Musta’simi in the 7th century AH, brought

calligraphy to new heights of ingenuity, recognition and popularity.

|

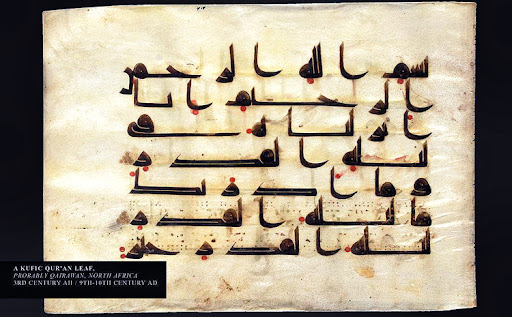

| A Kufic Quran Leaf, probably Qairawan, North Africa. 3rd Century AH / 9th – 10th Century AD |

Extending from manuscripts, calligraphy was soon used on a wide range

of artefacts including metalwork. ceramics, testes, glasswork and

glazed tiles. The Arabic alphabet, through the expansion of Islamic

culture and religion, was and still is used to write a host of other

languages, particularly Persian; Ottoman Turkish and Urdu. Today,

calligraphic art is widely popular in Contemporary art production

throughout the Islamic world.

Metalwork

|

| A Mamluk Silver Inlaid Brass Vase. Egypt. 7th century AH / 13-14th century AD |

Metalwork is amongst the most distinguished achievement in Islamic

art. From the early days of the Umayyad’s, artfully crafted metal wares

were produced in workshops throughout the Islamic world, leading to the

establishment of a rich tradition that persists today.

|

| A Silver Inlaid Brass Bowl. West Iran. 8th century AH / 14th Century AD |

Inspired by a quest for beauty and

precision in everyday objects, works on metal became an outlet for

aesthetic imagination and skilful craftsman- ship. From the 4th to 14th

AH, Syria, Egypt. Khorasan and Mesopotamia were among the main

production centers of Islamic metalwork. A large variety of items,

including vessels. lamps, armour, inkwells and incense burners were

manufactured by casting or working metal into intricate shapes of all

sizes. These artefacts would then be decorated and sometimes

embellislied with elegant inscriptions. Occasionally, objects were

inlaid with gold, silver or precious stones. An important part of the

beauty of Islamic metalwork lies in the harmonious treatment of

proportions. Through the careful study of decorative and manufacturing

techniques, artisans managed to create functional works of exquisite

beauty.

|

| A Safavid Cut Steel Panel. Iran. Late 10th century AH / 16th century AD |

Glass, Glazed Tiles and Ceramics

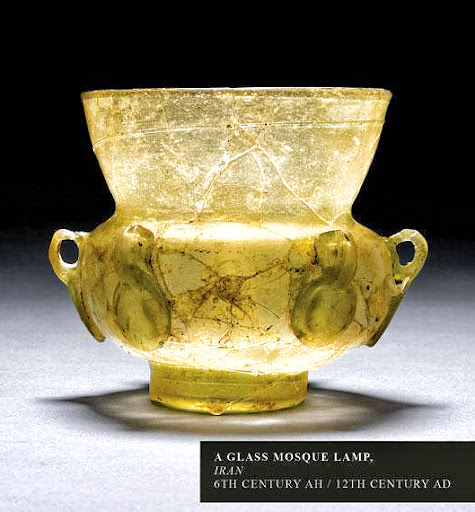

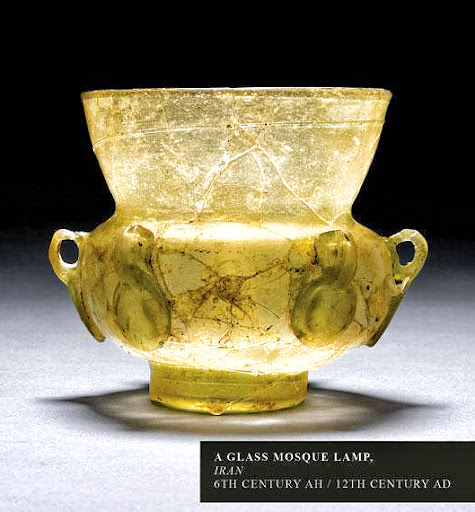

|

| A Glass Mosque Lamp. Iran. 6th century AH / 12th century AD. |

Light associated with the light of the heavens and the radiance of

the divine essence, has always played an important role in Islamic

Culture. Islamic artists and craftsmen wishing to imbue their working

with such meanings paid particular attention to bright materials and

luminous surfaces.

|

| A Moudled Pottery Vessel. Iran. Circa 596 AH / 1200 AD |

In Iran, the Ottoman Empire and Syria, walls were covered with glazed

and gleaming tiles decorated with geometric patterns and highly

stylised floral and foliate motifs. Although the production of tiles was

prominent throughout the Islamic world, Safavid and Iznik tiles were

particularly popular and are considered to be extraordinary examples of

pottery.

Inspired by Roman techniques, early Islamic glasswork was first

developed in Egypt and Syria . Initially stained or lustre-painted, by

the 3rd century AH the decoration of glasswork entailed intricate

incisions and complex relief patterns. These methods were later

perfected during the Fatimid and early Ayyubid periods. Influenced by

late Sasanian practices, the carved crystals of Fatimid Egypt and the

delicate and colourful carved glasses produced between the 4th and 6th

century AH in Nishapur and Syria, are amongst the best examples of

glasswork.

|

| A Samanid Pottery Dish. Central Asia. 4th Century AH / 10th Century AD |

The earliest examples of Islamic ceramics closely resemble the

alkaline glazed vessels produced in Egypt during the 4th millennium BC,

Known as ‘ Egyptian faince’. This type of earthen ware continued to be

manufactured in the Parthian and Sasanian Empires and its style remained

unchanged for centuries. In the 2nd century AH artisans of the early

Abbasid period introduced new techniques that would transform Islamic

pottery. Production centres spread from Samarkand to Mesopotamia,

Anatolia, Syria, Northern Africa and Andalusia. From the slip-painted

wares of the Samanid period to the late Iznik polychrome pottery of the

Ottoman Empire, the Islamic world fashioned incredibly fine examples of

ceramics and pioneered the vast array of decorative styles and designs

that have influenced ceramic production around the world.

Coins and Jewellery

Islamic coins were first produced during the Umayyad Caliphate and

decorated by two horizontal lines and one or more curved lines on the

rim. Although the use of these geometrically decorated examples columned

for several centuries, calligraphy devices were eventually adopted.

These evolved from simple inscriptions in Kufic to more complex designs

in Thuluth and Nastaliq scripts which occasionally adorned valuable

Islamic gold coins.

Ornaments and jewellery were also admired throughout the Islamic

world and their design and production became an important industrial,

artistic and scientific profession. Precious stones and minerals were

carefully studied by Scholars such as Abu Rayhan al-Biruni who wrote a

treatise on mineralogy and gems as early as the 4th Century AH. These

first interpretations were very influential, affecting the way a

particular stone was handled, worked and valued.

|

| An Impressive Diamond, Spinel and Enamel Sarpech. Mughal India, Deccan. Circa 1163 AH / 1750 AD. |

The rich design and fine quality of earrings, bracelets, rings and

necklaces produced by Islamic jewellers have been admired by European

travellers for centuries and are still a source of inspiration in the

design of modem jewellery.

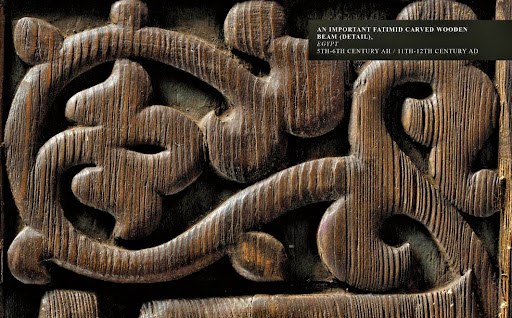

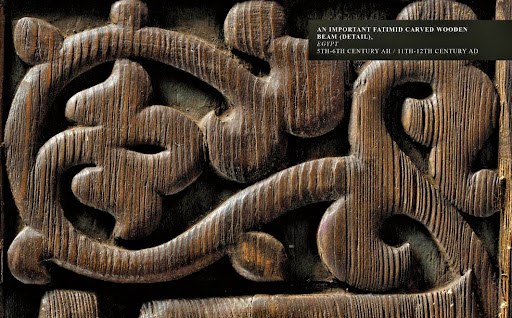

Woodwork

|

| An Ottoman Inlaid Jewellers Chest. Turkey. 17th century AD / 11th century AH. |

Relatively soft and easy to carve, wood was an important medium in

the production of Islamic art. Doors, tables. coffins, boxes and

cabinets were decorated with carved designs and inlaid with ivory and

ebony. Inlaid doors came to be seen as the best examples of elaborate

woodwork and craftsmanship. Their long and narrow panels accommodated

spectacular spiral patterns; arabesques and carved inscriptions of the

highest intricacy.

|

| A Fatimid Carved Wooden Beam (detail). Egypt. |

During the 8th and 9th century AH, woodwork became more complex and

delicate. Artists intertwined writings in Naskhi and Thuluth scripts

with decorative vegetal and bird patterns. Such works, produced in large

quantities in Mongolian India, the Ottoman Empire. Syria and Egypt

helped develop a common aesthetic language rooted in geometric designs,

floral motifs and calligraphic devices.

These patterns were similarly employed between 7th and 9th century AH

in Nasrid Spain, where micro mosaic decoration was practised and

perfected influenced by the Islamic tradition from the Umayyad period of

embellishing walnut with carved ivory. Nasrid woodwork was typically

inlaid with ivory, bone, metal and mother-of-pearl. This technique

persisted after the Christian Reconquista of the Iberian Peninsula and

can be seen in post Renaissance European furniture.

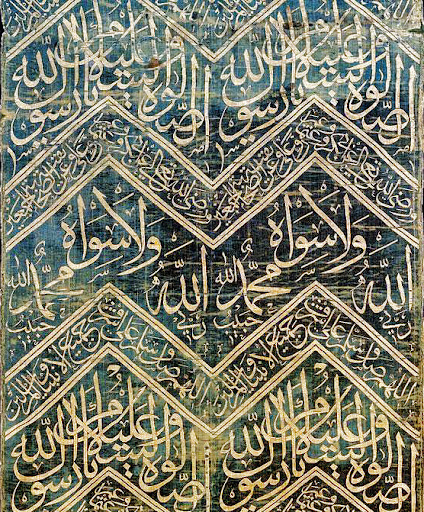

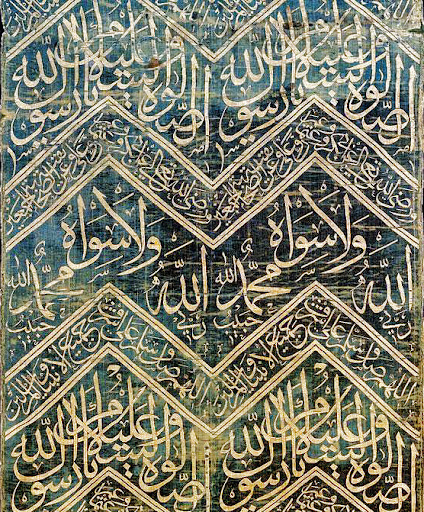

Textiles

|

| An Ottoman Curtain From the Tawassul at Medina (detail). Turkey. 13th century AH / 19th century AD |

The art of weaving in the Islamic world evolved from the simple forms

reflected in the earliest surviving textiles to the sophisticated

patterns and delicate textures that characterized production between the

8th and 11thCenturies AH.

Initially common in tomb covers, woven or embroidered inscriptions

became increasingly complex during the 5th and 6th century AH and played

important role in decorating the textiles produced in Fatimid Egypt and

Mesopotamia. Highly-stylised calligraphic designs complimented the

animal and bind patterns drawn from earlier Sasanid textile medallions.

|

| An Ottoman Woven Silk Tomb Cover. Turkey. 12th century AH / 18th century AD. |

During the 10th century AH, silk textiles adorned with rich patterns

and colours were developed the Ottoman Empire. Brocades and velvets were

woven with exceptional skill and decorated with floral designs, Both

magnificent curtains for the tomb of the Prophet Muhammad, Peace Be Upon

Him, and monumental hizamat for the Holy Ka’ba at Mecca were

embroidered with gold and silver thread on large silk and velvet

shrouds.

Demand in the West was high for textiles designed and woven in the

Islamic world, particularly for decorated Persian, Indian and Ottoman

silks. These had an undeniable influence on the history of textile

production throughout the world and were frequently imitated.

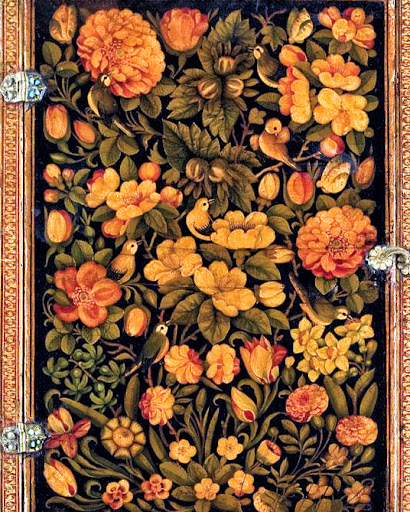

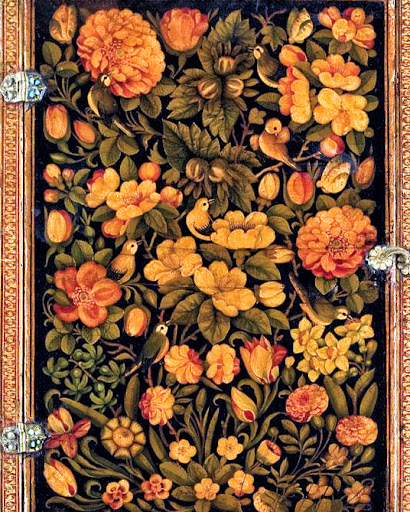

Lacquer

|

| A Polychrome Lacquer Vanity Case with Mirror. Iran. 12th Century AH / 18th century AD. |

Although painting glazed surfaces on dense cardboard dates back to

the5th century AH, Islamic lacquer truly bloomed between the 10th and

14th century AH. This practise involved covering papier-mache artefacts

with layers of lacquer, which were then decorated with miniature

pointings or illumination and staled with bright coin of varnish.

|

| A Polychrome Lacquer Wooden Casket. Iran. |

Lacquer was similarly popular in China and Japan, although the

methods and variety of artefacts used in the Islamic world considerably.

Associated with Iranian polychrome work on pen cases and boxes, Islamic

lacquer was also predominant in the production of bookbindings,

mirror-cases and caskets. Images of birds and flowers were usually used

when decorating Qur’an and religious bookbinding. The subject matter and

styles of these varies greatly. Depending on the client’s tastes and

the artist’s area of expertise, works might have depicted lyrical

portraits, landscapes, battle and burning scenes or royal gatherings.

Lacquer production was increasingly prominent frail the second half

of the 10th century to the 13th century AH. Court artists, led by

Muhammad Zaman in the 11th century AH; introduced figural miniature

paintings that were produced in great numbers in Isfahan. Typically

found on pen boxes sold in Iran, their influence extended far beyond

lite Islamic world and to Russia in particular.

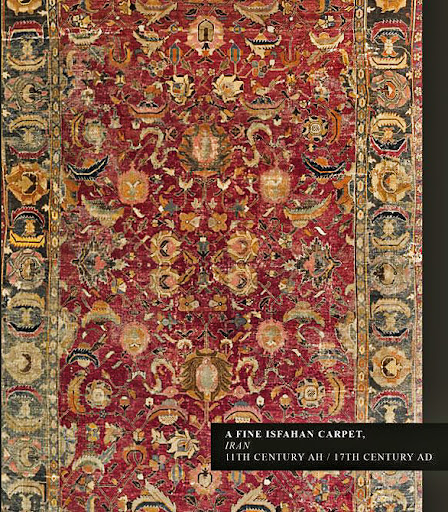

Carpets

|

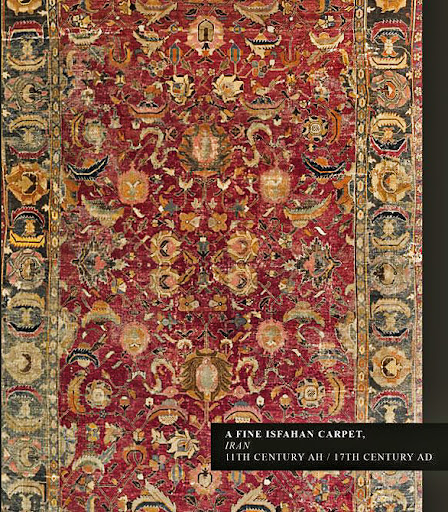

| A Fine Isfahan Carpet, Iran. 11th century AH / 17th century AD. |

There are unfortunately very few surviving examples of early Islamic

rugs and carpets, most probably due to the gradual erosion caused by use

over time and the particular sensitivity of wool, silk and other

materials used in their production. Written accounts, however, confirm

that carpet weaving was widely practised and that those in charge of

their design were ranked amongst the most important artists of their

time.

Until the end of the 9th century AH, rugs and carpets, were mostly

decorated with geometric patterns, gradually evolving to include

Spi¬rals, central medallions and four-sided triangles or lachaki. Later

designs were more figurative, incorporating stylised depletions of

animals and floral motifs.

|

| A Heriz Carpet. Northwest Iran. Circa 1308 AH / 1890 AD. |

Iran. India, Egypt, Anatolia and the Caucasus were the main centres

for the design and production of valuable carpels. Encouraged by

increasingly high demand, carpet workshops across the Islamic world

expanded their production to include silk as well as wool. Revered for

the quality of their execution, the harmony of their patterns and the

colours of these carpets were globally acclaimed and traded by

travellers, who exported Item to Europe and America.

1 comments:

The designs are grand. I love it but I don't have an elegant house.:)

Vinyl flooring perth

Post a Comment