Anne Gottsdanker was a chipper 5-year-old Santa Barbara girl 50 years ago, when her family doctor gave her one of the first of the newly approved Salk polio shots.Manufactured by

Cutter Laboratories in Berkeley, the vaccine came from two batches later found to be contaminated with live polio virus.

Gottsdanker came down with a flu-like illness during a family vacation to Calexico, on the Mexican border. She has been paralyzed ever since.

As a youngster, Gottsdanker dreamed of becoming a veterinarian, but vet schools weren't accepting women on crutches. Today, she is a college professor who motors about in an electric wheelchair and shares her home with her husband, teenage daughter, two dogs, four cats and a snake.

"Having polio, or any physical limitation, changes what you do in your life," she said during an interview in the kitchen of her home. "You reassess, and you end up doing what you're good at."

The first cases of polio in children who received the tainted vaccine were reported to regulators on April 25, 1955 - two weeks after the nation began a drive to vaccinate millions of schoolchildren. Before it was over, 164 people would suffer permanent paralysis from the Cutter vaccine or from the outbreak of polio triggered by it. Ten others died.

For a brief period, the “Cutter Incident” shut down the ambitious vaccination program and threatened to scuttle the effort that ultimately eliminated polio from the United States. The accidental paralysis of those healthy children is now all but forgotten, but University of Pennsylvania pediatrician Dr.

Paul Offit called it “one of the worst pharmaceutical disasters in U.S. history.”

His account marking the 50th anniversary of the Cutter Incident was published in the April 7 issue of the

New England Journal of Medicine and is the topic of a book coming out in September.

Gottsdanker’s parents eventually sued Cutter, hiring famed San Francisco attorney

Melvin Belli to represent their daughter. Her court victory rippled through the judicial system, its impact reverberating to this day.

A half-century after she was paralyzed, Gottsdanker, 55, pursues an active life in Lancaster, a windswept high-desert suburb north of Los Angeles.

“I used to have a lot of anger, but I don’t anymore,” she said. “That’s old. It’s ancient history.”

In 1955, she was unable to move her arms or legs in her hospital bed. But she eventually emerged with leg braces and crutches. In a world that did not accommodate disabilities, she earned a bachelor’s degree at Oregon’s

Reed College, a master’s at UC Santa Barbara and a doctorate from

Arizona State University.

Professor and mother

Now a professor at

Antelope Valley Community College, Gottsdanker teaches reading skills to students at the college and trains other teachers in the field. The mother of daughters ages 16 and 21, she plays classical music on an upright Baldwin piano, travels on camping trips and, until recently, rode all-terrain vehicles in the surrounding hills.

She raised her daughters by herself after her first marriage ended in divorce. Today, she is happily married to telecommunications engineer

Mike Rees.

Their home is lined with bookshelves. When she was growing up with polio, she read 12 books a week. Today, she teaches, among other subjects, speed reading.

“Life is interesting,” she said. “There’s too much to do than to just sit around.”

Six months ago, however, she set aside her crutches for a motorized wheelchair. Fifty years of limited mobility can take a toll on the muscles, bones and joints that make up for limbs that failed.

Gottsdanker must soon undergo two operations to relieve chronic pain in her back. Doctors have told her she must stop riding her ATV, and she may need to take break from teaching this fall to recover from the surgeries.

“You wish you could do things you can’t do,” Gottsdanker said matter-of- factly as she maneuvered her chair about the kitchen. But I do what I can

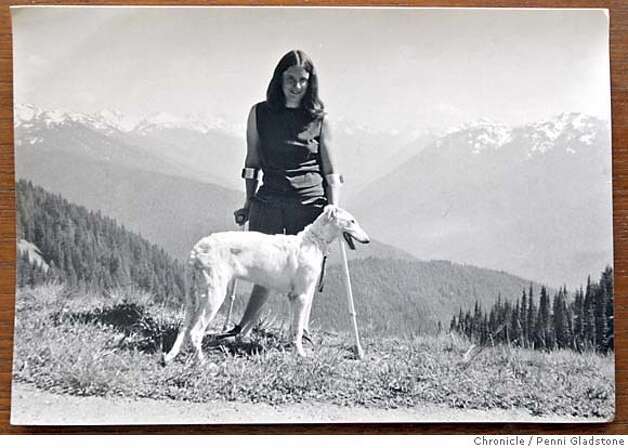

CUTTER209PG.JPG age 20 or 21 stands on a mountain top in the Olympic Penninsula. .April 25 is the 50th anniversay of an event that became known as the Cutter Incident. The new Salk polio vaccine had been approved two weeks earlier, and millions of school children were being vaccinated. On April 25 came the first reports of children coming down with polio-like symptoms in the arms where they had their shot. It turned out that 120,000 doses made by Cutter Laboratories in Berkeley contained LIVE virus. In the end at least 160 children were permanent paralyzed, 10 died, and perhaps 40,000 experienced less serious bouts with the virus. Anne Gottsdanker was a five year old girl whose right leg was paralyzed, and her parents filed a lawsuit that became a landmark case in pharmaceutical company liability law. The San Francisco Chronicle, Penni Gladstone Photo taken on 4/13/05, in Lancaster, Photo: Penni Gladstone

CUTTER209PG.JPG age 20 or 21 stands on a mountain top in the Olympic Penninsula. .April 25 is the 50th anniversay of an event that became known as the Cutter Incident. The new Salk polio vaccine had been approved two weeks earlier, and millions of school children were being vaccinated. On April 25 came the first reports of children coming down with polio-like symptoms in the arms where they had their shot. It turned out that 120,000 doses made by Cutter Laboratories in Berkeley contained LIVE virus. In the end at least 160 children were permanent paralyzed, 10 died, and perhaps 40,000 experienced less serious bouts with the virus. Anne Gottsdanker was a five year old girl whose right leg was paralyzed, and her parents filed a lawsuit that became a landmark case in pharmaceutical company liability law. The San Francisco Chronicle, Penni Gladstone Photo taken on 4/13/05, in Lancaster, Photo: Penni Gladstone

Printable Version

Printable Version Email This

Email This Font

Font

0 comments:

Post a Comment