The Times – April 22, 1938 obituary of Allam Iqbal. Nothing really new but you can try to see how the British viewed him.

(Most newspaper archives are available online so you can see other events for yourself)

SIR MUHAMMAD IQBAL

THE POET OF ISLAM

Sir Muhammad Iqbal, of Lahore, whose death at the age of 62 is announced by a Reuter message from Lahore, was the greatest Urdu and Persian poet of his day, and his reputation in the West might have been comparable to that of his great Indian contemporary Tagore had translations of his work into English been more frequent. He exercised an enormous influence on Islamic thought, and was an eloquent supporter of the rights and interests of his fellow Indian Muslims.

Iqbal was greatly influenced as a student at Lahore University by that ripe Islamic scholar Sir Thomas Arnold, and for seven years he was Professor of Philosophy at the Govern¬ment College Lahore.

He went to Cambridge in 1905 and read Western philosophy at Trinity College, under the direction of the late Dr. McTaggart, for the Philosophical Tripos, in which he obtained his degree by research work. In J908 he was called to the Bar by Lincoln’s Inn and did some practice in Lahore. The Munich University conferred on him the Ph.D. for a dissertation on the development of metaphysics in Persia. He developed a philosophy of his own, which owed much to Nietzsche and Bergson, while his poetry often reminded the reader of Shelley. The Asrar-i-Khudi (" Secrets of the Self "), published in Lahore in 1915, while giving no systematic account of his philosophy, put his ideas in a popular and attractive form. Professor R. A. Nicholson, of Cambridge, was so impressed by it that he obtained the leave of the poet to translate it into English, and the rendering was published in 1920.

Western readers found him to be an apostle. if not to his own age, then to posterity, and after the Persian fashion he invoked the Saki to fill his cup with wine and pour moonbeams into the dark night of his thought. He was an Islamic enthusiast, inspired by the vision of a New Mecca, a world-wide, theocratic, Utopian State in which all Muslims, no longer divided by the barriers of race and country, should he one. His ideal was a free and inde¬pendent Moslem fraternity, having the Ka’aba as its centre and knit together by love of Allah and devotion to the Prophet. In his Rumuz-e-Bekhudi (" The Mysteries of Selfless¬ness ") (1916) he dealt with the Iife of the Islamic community on those lines, and he allied the cry "Back to the Koran" with the revolutionary force of Western philosophy, which he hoped and believed would vitalize the movement and ensure its triumph. He, felt that Hindu intellectualism and Islamic pantheism had destroyed the capacity for action based on scientific observation and interpretation of phenomena which distinguished the Western peoples and "especially the English". But he was severely critical of Western life and thought on the ground of its materialism. Holding that the full development of the individual presupposes a society, he found the ideal society in what he considered to be the Prophet's conception of Islam. In 1923 he published Piyam-i-Mashriq ("The Message of the East ") and addressed the modern world at large in reply to Goethe's homage to the genius of the East. Two years later came Bang-i-Dira (" The Call to March "), a collection of his Urdu poems written during the first 20 years of the century. This was followed by a new Persian volume of which the title stood for "Songs of a Modern David,"

A poet with his gifts and his theme could not fail to influence thought in an India so politically minded as that of our day. He took some part in provincial politics being a member of the Punjab Legislature in 1925-28. He was on the British Indian delegation to the second session of the Round Table Conference in London in 1931. His authority was cited, not without some justification, for a theory of Islamic political solidarity in Northern India which might conceivably be extended to adjacent Moslem States. In 1930 he publicly advocated the formation of a North-West Indian Moslem State by the merging of the Moslem Provinces within the proposed All-India Federation. But his real interests were religious rather than political. A notable work published in 1934 reproduced a series of lectures by the poet on “The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam." Therein he I sought to reconcile the carrying out of modern reforms, as in Turkey, with the claims of the Shari’at. The lectures went to show "that soundness and exactitude of historical judgment were not his special endowment. The fact was that in maturity as in youth he sought to reconcile the most recent of Western philosophical systems, into which he gathered the latest scientific conclusions, with the teaching of the Koran. Like his earlier work the book was marked by penetrating and noble thought, though the connexion of his argument was somewhat obscure.

He was knighted in 1923, and the Punjab University made him an honorary D.Litt. in 1933. He was elected Rhodes Memorial Lecturer at Oxford University for 1935. For a long time he had been in indifferent health, and he became increasingly dreamy and mystical.

Monday, April 30, 2012

Zauq e Khudai - Salute to the men in Khaki

We have not forgotten our Shuhada. Today is day to remember our Shuhada who remained true to the Ummat e Rasul (sm) and Pak Sarzameen and defended the honor of our sisters and daughters. Mubarak to this millat that it has sons and brothers in khaki who are recreating the romance of Khalid, Salahuddin, Tariq, Tipu and Ghaznavi. Pak army, we love you. Stay blessed. We stand united with you on our march towards Delhi in the promised Ghazwa e Hind!

Sunday, April 29, 2012

The Farjam Collection of Islamic Art

The Islamic section of the collection spans the entire history of Islam, bringing together items produced throughout the vast region between Andalusia and Mughal India. Its treasures include Quranic manuscripts, miniatures and illustrated books on science, mathematics and poetry, as well as finely-decorated metalwork, lacquer, glasswork, tiles, glazed pottery, woodwork, textiles, coins, jewelry, and fine carpets.The Farjam Collection is one of the most impressive privately-owned collections in the world today. Featuring Islamic and pre-Islamic art, Contemporary Middle-Eastern art and International Modern and Contemporary Art, the Collection is born of a passion for art, exploration and travel, reflecting the affinities and tastes of a seasoned collector. Through a timeless journey into art, it embodies the fusion of cultures and traditions between East and West.

The Holy Quran

| ||||

|

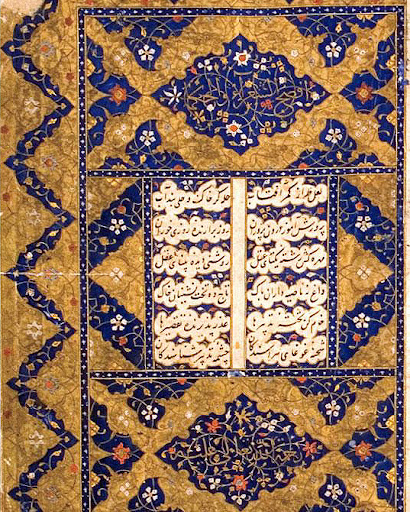

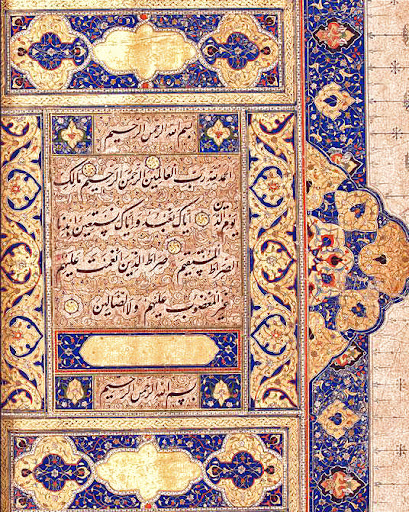

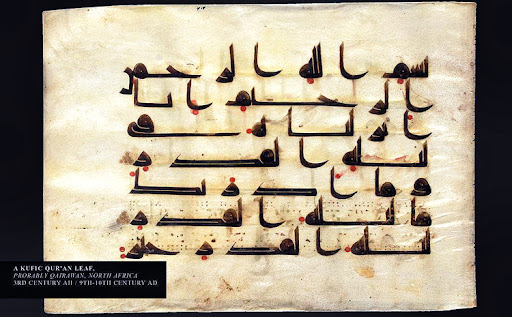

Qur’anic manuscripts and calligraphic forms

with which the word of God was recorded were of great importance. As a

means to express praise, faith and adhesion to Islam, transcriptions of

the Qur’an were highly valued. Over the centuries, a variety of scripts

were used, including Hijazi, Kufic, Thuluth, Muhaqqaq. Nakshi and

Rihani. Each followed strict rules of design put forth by master

calligraphers as early as she the 4th century AH. Decorated with

elegance, care and sincerity, each Leaf reflects the scribe’s mastery of

proportionality and the efforts of a number of other specialists from

paper makers to bookbinders.

|

| An Illuminated Quran, Iran. Dated 734 AH / 1333 -1334 AD. |

|

| An Illuminated Quran (detail). Iran. Dated 1243 AH / 1827 AD. |

The Manuscripts

While early secular manuscripts from the Islamic world were simple and unadorned, they became increasingly stylized and ornate as the techniques employed in Qur’ans were gradually applied to a wider variety of texts. During the 6th and 7th centuries, as Baghdad became an important cultural centre, numerous scholars participated in the production of Scientific and literary words on subjects such as mathematics, a sinology, medicine, history, and poetry. From the 7th century onwards, such texts were accompanied by detailed paintings and images. These complemented the art of calligraphy and added a new visual dimension to the manuscripts, different from traditional Qur’anic illumination.Secular books and manuscripts were treated with such skill and technique that some examples are considered not only as valuable documents, but also as artworks in their own right. The striking delicacy of later pieces made manuscript illustration one of the most lauded forms of Islamic art and helped disseminate the culture and religion of Islam throughout the world.

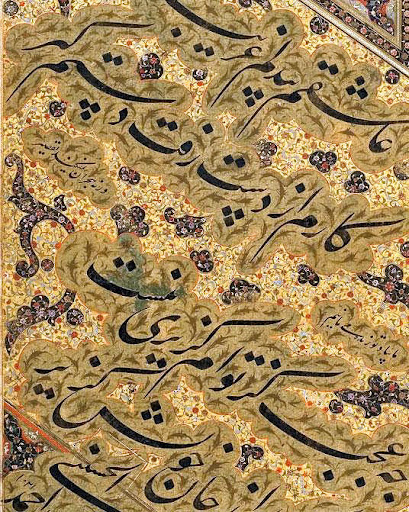

Calligraphy

|

| A Calligraphic Panel in Nastaliq Script. Iran. Dated 1021 AH / 1612 AD. Signed Ahmad Al-Hosseini |

|

| A Kufic Quran Leaf, probably Qairawan, North Africa. 3rd Century AH / 9th – 10th Century AD |

Metalwork

|

| A Mamluk Silver Inlaid Brass Vase. Egypt. 7th century AH / 13-14th century AD |

|

| A Silver Inlaid Brass Bowl. West Iran. 8th century AH / 14th Century AD |

Inspired by a quest for beauty and

precision in everyday objects, works on metal became an outlet for

aesthetic imagination and skilful craftsman- ship. From the 4th to 14th

AH, Syria, Egypt. Khorasan and Mesopotamia were among the main

production centers of Islamic metalwork. A large variety of items,

including vessels. lamps, armour, inkwells and incense burners were

manufactured by casting or working metal into intricate shapes of all

sizes. These artefacts would then be decorated and sometimes

embellislied with elegant inscriptions. Occasionally, objects were

inlaid with gold, silver or precious stones. An important part of the

beauty of Islamic metalwork lies in the harmonious treatment of

proportions. Through the careful study of decorative and manufacturing

techniques, artisans managed to create functional works of exquisite

beauty.

|

| A Safavid Cut Steel Panel. Iran. Late 10th century AH / 16th century AD |

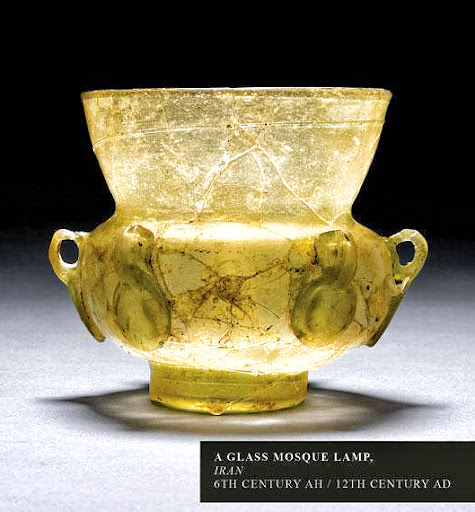

Glass, Glazed Tiles and Ceramics

|

| A Glass Mosque Lamp. Iran. 6th century AH / 12th century AD. |

|

| A Moudled Pottery Vessel. Iran. Circa 596 AH / 1200 AD |

Inspired by Roman techniques, early Islamic glasswork was first developed in Egypt and Syria . Initially stained or lustre-painted, by the 3rd century AH the decoration of glasswork entailed intricate incisions and complex relief patterns. These methods were later perfected during the Fatimid and early Ayyubid periods. Influenced by late Sasanian practices, the carved crystals of Fatimid Egypt and the delicate and colourful carved glasses produced between the 4th and 6th century AH in Nishapur and Syria, are amongst the best examples of glasswork.

|

| A Samanid Pottery Dish. Central Asia. 4th Century AH / 10th Century AD |

Coins and Jewellery

Coins and Jewellery

Ornaments and jewellery were also admired throughout the Islamic world and their design and production became an important industrial, artistic and scientific profession. Precious stones and minerals were carefully studied by Scholars such as Abu Rayhan al-Biruni who wrote a treatise on mineralogy and gems as early as the 4th Century AH. These first interpretations were very influential, affecting the way a particular stone was handled, worked and valued.

|

| An Impressive Diamond, Spinel and Enamel Sarpech. Mughal India, Deccan. Circa 1163 AH / 1750 AD. |

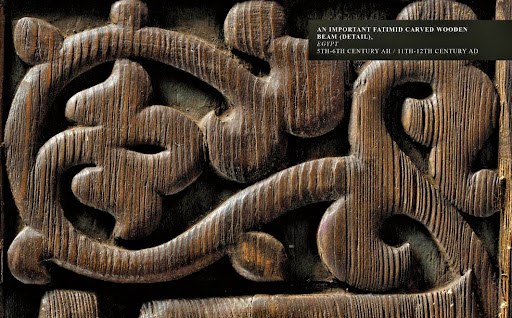

Woodwork

|

| An Ottoman Inlaid Jewellers Chest. Turkey. 17th century AD / 11th century AH. |

|

| A Fatimid Carved Wooden Beam (detail). Egypt. |

These patterns were similarly employed between 7th and 9th century AH in Nasrid Spain, where micro mosaic decoration was practised and perfected influenced by the Islamic tradition from the Umayyad period of embellishing walnut with carved ivory. Nasrid woodwork was typically inlaid with ivory, bone, metal and mother-of-pearl. This technique persisted after the Christian Reconquista of the Iberian Peninsula and can be seen in post Renaissance European furniture.

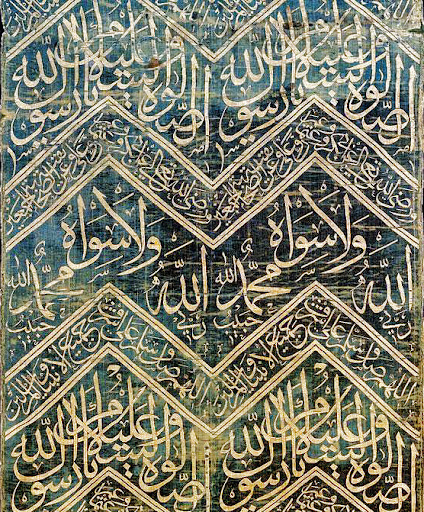

Textiles

|

| An Ottoman Curtain From the Tawassul at Medina (detail). Turkey. 13th century AH / 19th century AD |

Initially common in tomb covers, woven or embroidered inscriptions became increasingly complex during the 5th and 6th century AH and played important role in decorating the textiles produced in Fatimid Egypt and Mesopotamia. Highly-stylised calligraphic designs complimented the animal and bind patterns drawn from earlier Sasanid textile medallions.

|

| An Ottoman Woven Silk Tomb Cover. Turkey. 12th century AH / 18th century AD. |

Demand in the West was high for textiles designed and woven in the Islamic world, particularly for decorated Persian, Indian and Ottoman silks. These had an undeniable influence on the history of textile production throughout the world and were frequently imitated.

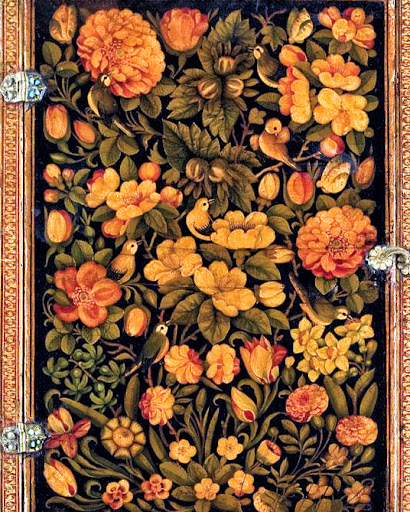

Lacquer

|

| A Polychrome Lacquer Vanity Case with Mirror. Iran. 12th Century AH / 18th century AD. |

|

| A Polychrome Lacquer Wooden Casket. Iran. |

Lacquer production was increasingly prominent frail the second half of the 10th century to the 13th century AH. Court artists, led by Muhammad Zaman in the 11th century AH; introduced figural miniature paintings that were produced in great numbers in Isfahan. Typically found on pen boxes sold in Iran, their influence extended far beyond lite Islamic world and to Russia in particular.

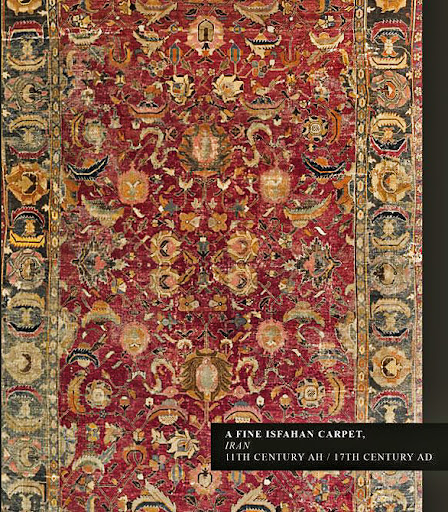

Carpets

|

| A Fine Isfahan Carpet, Iran. 11th century AH / 17th century AD. |

Until the end of the 9th century AH, rugs and carpets, were mostly decorated with geometric patterns, gradually evolving to include Spi¬rals, central medallions and four-sided triangles or lachaki. Later designs were more figurative, incorporating stylised depletions of animals and floral motifs.

|

| A Heriz Carpet. Northwest Iran. Circa 1308 AH / 1890 AD. |

Saturday, April 28, 2012

Muslims - Pioneer Physicians

In 1120, a Muslim doctor was on his way to see his patient, the

Almoravid ruler of Seville. By the side of the road he saw an emaciated

man holding a water jug. The man’s belly was swollen, and he was in

obvious distress.

In the East, the spread of Islam, beginning in the seventh century ce, sparked the assimilation of existing knowledge and its development in all branches of learning, including medicine. Arab conquerors rapidly absorbed much from their new subjects. Arabic became to the East what Latin and Greek had been to the West—the language of literature and of the arts and sciences, the common tongue of learned men from the Rann of Kutch to the French border—and the Hajj, or pilgrimage to Makkah, brought hundreds of thousands of pilgrims together each year, facilitating the exchange of ideas, knowledge and books.

Recognizing the importance of translating Greek works into Arabic to make them more widely available, the Abbasid caliphs Harun al-Rashid and his son, al-Ma’mun, sponsored a translation bureau in Baghdad—the Bayt al-Hikmah, or House of Wisdom—starting in the late eighth century, that sent agents throughout Muslim and non-Muslim lands in search of scholarly manuscripts in every language. Rendered into Arabic, these precious documents established a solid foundation for the Muslim sciences, not the least of which was medicine.

As in Greece, medicine in the Muslim world was based on the theory of the four humors that had been advanced by the second-century Greek physician Galen. Each of the four universal elements that comprised the world—earth, air, fire and water—was associated with one of the humors—blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile—whose various mixtures defined the different temperaments. When the body’s humors were in correct alignment, a person was healthy; when out of balance, he was sick. The task of the doctor, Galen wrote, was to restore this alignment by prescribing changes in diet, exercise or certain activities, or by taking other measures. For example, fever was caused by too much blood, and thus he prescribed bloodletting to remove the excess.

However incorrect, Galen’s essentially rationalist view of health and disease found favor in the East, where the Qur’an assured that “for every disease there is a cure.” Thus Muslim physicians saw themselves as healers and preservers of health rather than passive witnesses to events with supernatural causes.

While the translators in the House of Wisdom toiled, Muslim doctors developed the bimaristan—later simply maristan—the forerunner of today’s hospital. Open to all, it welcomed patients to be treated for, and recover from, a variety of ailments and injuries, including mental illness. The larger maristans were attached to medical schools and libraries, where prospective physicians were taught, examined and, as today, licensed. The maristan became the cradle of Islamic medicine and the means of its dissemination throughout the empire.

Like the hospital, pharmacy as a profession is also an Islamic innovation. In the maristans, trained pharmacists prepared and dispensed remedies that more often than not had some positive effects. Their extensive pharmacopeias detailed the geographical origins, physical properties and methods of application of everything found useful in the curing of disease. By al-Ma’mun’s time, the pharmacists (saydalani) were, like doctors, licensed professionals required to pass demanding examinations, and to protect the public from errors and incompetence, government inspectors monitored the purity of their ointments, pills, elixirs, confections, tinctures, suppositories and inhalants. In the maristan, the chief pharmacist held a rank equal to that of the chief of medicine.

But while Abbasid Baghdad, with the House of Wisdom and the first maristans, may have begun the golden age of Islamic medicine, the center of learning and progress began to shift westward in the eighth century, to al-Andalus, today’s southern Spain.

The Abbasids had taken power from the Damascus-based Umayyad dynasty. Abdulrahman, grandson of the 10th Umayyad caliph, escaped the massacre of his relatives and in 758 ce took asylum in Spain. Within a few years, this intrepid ruler had carved out a rival caliphate with its capital at Córdoba, and by the late 10th century Córdoba had surpassed Baghdad as the center of intellectual activity in the Islamic world.

Córdoba’s 70 libraries, 900 public baths, 300 mosques and 50 maristans were available to all of its one million residents. Córdoba’s university, founded in the eighth century, was a premier center of learning, and its library held at least 225,000 volumes. (At that time, the library of the University of Paris held some 400 volumes.) It drew scholars from all over Europe—one of them, Gerbert of Aurillac, later became Pope Sylvester ii, who replaced cumbersome Roman numerals with today’s “Arabic” numbers. Al-Andalus was soon home to accomplished and innovative philosophers, geographers, engineers, architects and physicians.

In the western caliphate, doctors differed from their eastern counterparts. Although Córdoba and Baghdad were in close contact intellectually, the western physicians exhibited more independence of thought than their more classics-bound eastern colleagues, offering no blind obedience to either Galen or the Canon of Ibn Sina, the 10th-century Bukhara-born physician who was the Arab world’s equivalent of Aristotle and Leonardo. Instead, they challenged and rejected both when their own experience justified it. Their writings and research showed their preference for the concise, the brief and the exact, as contrasted with the discursive, often hair-splitting, subtleties preferred by the savants of the East.

While the western Islamic world produced hundreds of insightful and even brilliant medical men between the ninth and 15th centuries, five stand at the pinnacle of medicine during their eras, and their influences reverberate even now, more than a millennium later.

Al-Zahrawi only wrote one book, Kitab al-Tasrif li-man ‘Ajizja ‘an

al-Ta’lif (The Arrangement [of Medical Knowledge] for One Who is Unable

to Compile [a Manual for Himself]), a compendium of 30 volumes on

medicine, surgery, pharmacy and other health topics compiled during a

50-year career. Its last volume, the 300-page On Surgery, was the first

book to treat surgery as a separate subject and the first illustrated

surgical treatise. Covering ophthalmology, obstetrics, gynecology,

military medicine, urology, orthopedics and more, it remained a standard

surgical reference in Europe until the late 16th century.

Al-Zahrawi described a vast repertoire (see “On the Cutting Edge,” at

left) of procedures, inventions and techniques, including

thyroidectomy, extraction of cataracts and an innovative method of

removing kidney stones by diversion through the rectum that dramatically

reduced the mortality rate for the procedure, compared to the method

Galen recommended.

The Arrangement of Medical Knowledge was the earliest text to deal with dental surgery in detail, including reimplantation of dislodged teeth. It also described the carving of false teeth from animal bone, as well as how to correct non-aligned or deformed teeth. Al-Zahrawi also detailed procedures still used by today’s dental hygienists to remove calculus deposits from teeth.

More prosaically, al-Zahrawi used ink preoperatively to mark the incisions on his patients’ skin, now a standard procedure worldwide. He was the first to use catgut for internal sutures, silk for cosmetic surgery and cotton as a surgical dressing. He described, and probably invented, the plaster cast for fractures—a practice not widely adopted in Europe until the 19th century. He produced annotated diagrams of more than 200 surgical instruments, many of which he devised himself. His meticulous illustrations, intended as both teaching tools and manufacturing guides, are the earliest known and possibly the first ever such published diagrams. His best-known inventions were the syringe, the obstetrical forceps, the surgical hook and needle, the bone saw and the lithotomy scalpel—all items in use today in much the same forms.

Ibn Zuhr, however, did not merely follow in his ancestors’ footsteps. He became the first Muslim scientist to devote himself exclusively to medicine, and his several major discoveries were chronicled in his books Kitab al-Taysir fi ‘l-Mudawat wa ‘l-Tadbir (Practical Manual of Treatments and Diets) and a treatise on psychology whose title translates Book of the Middle Course Concerning the Reformation of Souls and Bodies, as well as Kitab al Aghdiya (Book on Foods) that describes the health effects of diets, condiments and drinks.

In this body of work, one of his smaller but most effective accomplishments was proof that scabies is caused by the itch mite, and that it can be cured by removing the parasite from the patient’s body without purging, bleeding or any other (often painful) treatments associated with the four humors. This discovery sent a shudder through medical science, for it unshackled medicine from strict reliance on the theory of humors and, with that, blind acceptance of Galen and Ibn Sina.

Ibn Zuhr also wrote about how diet and lifestyle can help a person avoid developing kidney stones. He gave the first accurate descriptions of neurological disorders, including meningitis, intracranial thrombophlebitis and mediastinal tumors, and he made some of the first contributions to what became modern neuropharmacology. He provided the first detailed report of cancer of the colon. Ibn Zuhr was the first to explain how to provide direct feeding through the gullet or rectum in cases where normal feeding was not possible—a technique now known as parenteral feeding.

Ibn Zuhr introduced the experimental method into surgery, using animals as test subjects—using, for example, a goat to prove the safety of a tracheotomy procedure he devised. He also performed post-mortems on sheep while doing clinical research on how to treat ulcerating diseases of the lungs. Ibn Zuhr is the first physician known to have performed human dissection and to use autopsies to enhance his understanding of surgical techniques.

Ibn Zuhr established surgery as an independent field by introducing a training course designed specifically for future surgeons before allowing them to perform operations independently. He differentiated the roles of a general practitioner and a surgeon, drawing the metaphorical “red lines” at which a physician should stop during his management of a surgical condition, thus further helping define surgery as a medical specialty. He was also among the first to use anesthesia, performing hundreds of surgeries after placing sponges soaked in a mixture of cannabis, opium and hyoscyamus (henbane) over the patient’s face.

Not least, by seeing to it that both his daughter and his granddaughter went into medicine, he became a pioneer in a different way. Though largely limited to obstetrics, these women began a tradition in the Muslim world that accepted females as medical doctors 700 years before Johns Hopkins University graduated the first American female physician.

When he was 10 years old, the less-than-tolerant Almohads conquered Córdoba. They offered the city’s Jews and Christians the choice of conversion to Islam, exile or death. Maimonides’s family chose exile, and they eventually settled near Cairo. When family tragedy reduced them to penury, he took up the practice of medicine.

Maimonides wrote 10 known medical works in Arabic. They describe, among much else, conditions including asthma, diabetes, hepatitis and pneumonia. They emphasize moderation and a healthy lifestyle. A doctor, he wrote, must be knowledgeable in many disciplines, treat the whole patient and not just the disease, heal both the body and the soul, and must himself be imbued with human and spiritual values, the foremost of which is compassion.

Throughout his medical works Maimonides often challenged what he called Galen’s “arrogant presumption” when it differed from his own experiences, leading to one of his key contributions: the idea that, in medicine, personal empirical experience trumps written authority. Nonetheless, his passion for order and learning led him to abridge the Roman physician’s massive literary output to a single book of key extracts that a physician could carry in his pocket. Though he was also a Talmudic rabbi, when it came to the understanding of disease, Maimonides was what today we would call a “natural scientist”—a strict empiricist—and he strove to clearly divorce medicine from religion. At a time when magic, superstition and astrology were all widespread in medical practice, his writings contain no references to these, nor to Talmudic medicine. That which is correct, he argued, is that which works.

He recognized furthermore the medical benefits of positive thinking, leading to an early form of psychosomatic medicine. Whether certain amulets or trinkets were anathema to his rational world view was unimportant compared to the needs of the patient. If they made the patient feel better, he wrote, then having them present was best “lest the mind of the patient be too greatly disturbed.”

At 29, he published the Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun Ibn Sina (Commentary on Anatomy in the Canon of Ibn Sina). The book described a number of his anatomical discoveries, including the earliest explanation of the pulmonary circulation of blood.

Ibn al-Nafis went on to show that the wall between the right and left

ventricles of the heart is solid and without pores, thus disproving

Galen’s teaching that the blood passes directly from the right to the

left side of the heart. Ibn al-Nafis then correctly stated that the

blood must pass from the right ventricle to the lungs, where its lighter

parts filter into the pulmonary vein to mix with air and then to the

left atrium and finally onward to the rest of the body. It was the first

time anyone was able to explain how air entered the blood.

Ibn al-Nafis also hinted at the existence of capillary circulation, arguing “there must be small communications or pores [manafidh] between the pulmonary artery and vein.” Though his hypothesis was limited to blood transit in the lungs, it would be confirmed for the entire body 400 years later when Marcello Malpighi described the action of capillaries. Moreover, after the 14th century, Ibn al-Nafis’s discovery was lost, and it was not until 1924, when Egyptian physician Muhyo al-Deen Altawi found a copy of the Commentary in Berlin’s Prussian State Library, that the full extent of Ibn al-Nafis’s work was understood—showing that it was he, and not William Harvey some four centuries later, who had discovered the circulatory system.

Unfortunately, Ibn al-Nafis’s fall into undeserved obscurity was not unique or even particularly unusual. Over those medieval centuries Muslim physicians by the tens of thousands, the great and the ordinary, lived and worked mostly outside centers of medical science. While they toiled, small groups of Christian and Jewish scholars also labored, filling for a coming era the roles of translators and disseminators that their Muslim predecessors had once filled for al-Ma’mun in Baghdad. Many were located along the porous, shifting, multicultural frontier with Spain where Toledo, Barcelona and Segovia offered them support; others gathered in the cities of France, Italy and Sicily that were touched by Islam. They too became cultural bridges, returning to a reawakening West both the intellectual foundations it had foregone nearly a millennium earlier and a rich legacy of discovery upon which today’s western medicine is founded.

The physicians who produced this legacy of discovery in the Muslim world devised techniques and further unraveled enduring mysteries of the human body and mind. They established hospitals and the professions of surgery, medicine and pharmacy, invented surgical instruments and applied empirical methods to test hypotheses. They separated religion from science and opened a door for women. Many of their precepts of personal health, diet and hygiene are common sense today. Perhaps most important of all, they re-taught European physicians that sickness is only a deviation from health, and that the role of medicine is to cure disease.

If any of this seems too easily self-evident to us, that is because progress turns yesterday’s discoveries into today’s everyday knowledge.

“Are you sick?” the doctor asked. The man nodded.While this demonstration of clear reasoning was taking place in Muslim Spain, medical practice in Christian Europe, hobbled by a mindset that would have seen the doctor’s work as a challenge to divine will, offered the sick little more than prayers and comfort, rather than medicine or treatments.

“What have you been eating?”

“Only a few crusts of bread and the water from this jug.”

“Bread won’t hurt you,” said the doctor. “It could be the water. Where are you getting it?”

“From the well in town.”

The doctor pondered a moment. “The well is clean. It must be the jug. Break it and find a new one.”

“I can’t,” whined the man, “This is my only jug.”

“And that thing bulging out there,” replied the doctor, pointing to the man’s midsection, “is your only stomach. It is easier to find a new jug than a new stomach.”

The man continued to protest, but one of the doctor’s servants picked up a stone and smashed the jug. A dead frog spilled out with the foul water.

“My friend,” the doctor said to the patient, “look what you have been drinking. That frog would have taken you with him. Here, take this coin and go buy a new jug.”

When the doctor passed by a few days later, he saw the same man sitting by the side of the road. His stomach had shrunk, he had gained weight, and his color was back. Seeing the doctor, the man heaped praise on him.

—attributed to Ibn Abi Usaybi’a, 13th century

In the East, the spread of Islam, beginning in the seventh century ce, sparked the assimilation of existing knowledge and its development in all branches of learning, including medicine. Arab conquerors rapidly absorbed much from their new subjects. Arabic became to the East what Latin and Greek had been to the West—the language of literature and of the arts and sciences, the common tongue of learned men from the Rann of Kutch to the French border—and the Hajj, or pilgrimage to Makkah, brought hundreds of thousands of pilgrims together each year, facilitating the exchange of ideas, knowledge and books.

Recognizing the importance of translating Greek works into Arabic to make them more widely available, the Abbasid caliphs Harun al-Rashid and his son, al-Ma’mun, sponsored a translation bureau in Baghdad—the Bayt al-Hikmah, or House of Wisdom—starting in the late eighth century, that sent agents throughout Muslim and non-Muslim lands in search of scholarly manuscripts in every language. Rendered into Arabic, these precious documents established a solid foundation for the Muslim sciences, not the least of which was medicine.

As in Greece, medicine in the Muslim world was based on the theory of the four humors that had been advanced by the second-century Greek physician Galen. Each of the four universal elements that comprised the world—earth, air, fire and water—was associated with one of the humors—blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile—whose various mixtures defined the different temperaments. When the body’s humors were in correct alignment, a person was healthy; when out of balance, he was sick. The task of the doctor, Galen wrote, was to restore this alignment by prescribing changes in diet, exercise or certain activities, or by taking other measures. For example, fever was caused by too much blood, and thus he prescribed bloodletting to remove the excess.

However incorrect, Galen’s essentially rationalist view of health and disease found favor in the East, where the Qur’an assured that “for every disease there is a cure.” Thus Muslim physicians saw themselves as healers and preservers of health rather than passive witnesses to events with supernatural causes.

While the translators in the House of Wisdom toiled, Muslim doctors developed the bimaristan—later simply maristan—the forerunner of today’s hospital. Open to all, it welcomed patients to be treated for, and recover from, a variety of ailments and injuries, including mental illness. The larger maristans were attached to medical schools and libraries, where prospective physicians were taught, examined and, as today, licensed. The maristan became the cradle of Islamic medicine and the means of its dissemination throughout the empire.

Like the hospital, pharmacy as a profession is also an Islamic innovation. In the maristans, trained pharmacists prepared and dispensed remedies that more often than not had some positive effects. Their extensive pharmacopeias detailed the geographical origins, physical properties and methods of application of everything found useful in the curing of disease. By al-Ma’mun’s time, the pharmacists (saydalani) were, like doctors, licensed professionals required to pass demanding examinations, and to protect the public from errors and incompetence, government inspectors monitored the purity of their ointments, pills, elixirs, confections, tinctures, suppositories and inhalants. In the maristan, the chief pharmacist held a rank equal to that of the chief of medicine.

But while Abbasid Baghdad, with the House of Wisdom and the first maristans, may have begun the golden age of Islamic medicine, the center of learning and progress began to shift westward in the eighth century, to al-Andalus, today’s southern Spain.

The Abbasids had taken power from the Damascus-based Umayyad dynasty. Abdulrahman, grandson of the 10th Umayyad caliph, escaped the massacre of his relatives and in 758 ce took asylum in Spain. Within a few years, this intrepid ruler had carved out a rival caliphate with its capital at Córdoba, and by the late 10th century Córdoba had surpassed Baghdad as the center of intellectual activity in the Islamic world.

Córdoba’s 70 libraries, 900 public baths, 300 mosques and 50 maristans were available to all of its one million residents. Córdoba’s university, founded in the eighth century, was a premier center of learning, and its library held at least 225,000 volumes. (At that time, the library of the University of Paris held some 400 volumes.) It drew scholars from all over Europe—one of them, Gerbert of Aurillac, later became Pope Sylvester ii, who replaced cumbersome Roman numerals with today’s “Arabic” numbers. Al-Andalus was soon home to accomplished and innovative philosophers, geographers, engineers, architects and physicians.

In the western caliphate, doctors differed from their eastern counterparts. Although Córdoba and Baghdad were in close contact intellectually, the western physicians exhibited more independence of thought than their more classics-bound eastern colleagues, offering no blind obedience to either Galen or the Canon of Ibn Sina, the 10th-century Bukhara-born physician who was the Arab world’s equivalent of Aristotle and Leonardo. Instead, they challenged and rejected both when their own experience justified it. Their writings and research showed their preference for the concise, the brief and the exact, as contrasted with the discursive, often hair-splitting, subtleties preferred by the savants of the East.

While the western Islamic world produced hundreds of insightful and even brilliant medical men between the ninth and 15th centuries, five stand at the pinnacle of medicine during their eras, and their influences reverberate even now, more than a millennium later.

”The Father of Surgery”

Born in 938 ce just north of Córdoba in Al Zahra, the royal city of Abdulrahman iii, Abu al-Qasim Khalaf ibn al-’Abbas was known to contemporaries as al-Zahrawi, and his name was Latinized to Albucasis. While little is known for certain about his personal life, his surgical acumen was unprecedented. |

| Al-Zahrawi’s annotated illustrations of surgical instruments were circulating in Europe in Latin translation in the 14th century. |

The Arrangement of Medical Knowledge was the earliest text to deal with dental surgery in detail, including reimplantation of dislodged teeth. It also described the carving of false teeth from animal bone, as well as how to correct non-aligned or deformed teeth. Al-Zahrawi also detailed procedures still used by today’s dental hygienists to remove calculus deposits from teeth.

More prosaically, al-Zahrawi used ink preoperatively to mark the incisions on his patients’ skin, now a standard procedure worldwide. He was the first to use catgut for internal sutures, silk for cosmetic surgery and cotton as a surgical dressing. He described, and probably invented, the plaster cast for fractures—a practice not widely adopted in Europe until the 19th century. He produced annotated diagrams of more than 200 surgical instruments, many of which he devised himself. His meticulous illustrations, intended as both teaching tools and manufacturing guides, are the earliest known and possibly the first ever such published diagrams. His best-known inventions were the syringe, the obstetrical forceps, the surgical hook and needle, the bone saw and the lithotomy scalpel—all items in use today in much the same forms.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Image via Wikipedia |

The Doctor of Seville

The doctor who observed, diagnosed and cured the man by the side of the road at the beginning of this article was Abu Marwan ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Zuhr, later Latinized to Avenzoar, who was born in 1091 ce in Seville. Since the Banu Zuhr, as his family was known, had already produced two generations of physicians (and would produce five more), there was no question about his career.Ibn Zuhr, however, did not merely follow in his ancestors’ footsteps. He became the first Muslim scientist to devote himself exclusively to medicine, and his several major discoveries were chronicled in his books Kitab al-Taysir fi ‘l-Mudawat wa ‘l-Tadbir (Practical Manual of Treatments and Diets) and a treatise on psychology whose title translates Book of the Middle Course Concerning the Reformation of Souls and Bodies, as well as Kitab al Aghdiya (Book on Foods) that describes the health effects of diets, condiments and drinks.

In this body of work, one of his smaller but most effective accomplishments was proof that scabies is caused by the itch mite, and that it can be cured by removing the parasite from the patient’s body without purging, bleeding or any other (often painful) treatments associated with the four humors. This discovery sent a shudder through medical science, for it unshackled medicine from strict reliance on the theory of humors and, with that, blind acceptance of Galen and Ibn Sina.

Ibn Zuhr also wrote about how diet and lifestyle can help a person avoid developing kidney stones. He gave the first accurate descriptions of neurological disorders, including meningitis, intracranial thrombophlebitis and mediastinal tumors, and he made some of the first contributions to what became modern neuropharmacology. He provided the first detailed report of cancer of the colon. Ibn Zuhr was the first to explain how to provide direct feeding through the gullet or rectum in cases where normal feeding was not possible—a technique now known as parenteral feeding.

Ibn Zuhr introduced the experimental method into surgery, using animals as test subjects—using, for example, a goat to prove the safety of a tracheotomy procedure he devised. He also performed post-mortems on sheep while doing clinical research on how to treat ulcerating diseases of the lungs. Ibn Zuhr is the first physician known to have performed human dissection and to use autopsies to enhance his understanding of surgical techniques.

Ibn Zuhr established surgery as an independent field by introducing a training course designed specifically for future surgeons before allowing them to perform operations independently. He differentiated the roles of a general practitioner and a surgeon, drawing the metaphorical “red lines” at which a physician should stop during his management of a surgical condition, thus further helping define surgery as a medical specialty. He was also among the first to use anesthesia, performing hundreds of surgeries after placing sponges soaked in a mixture of cannabis, opium and hyoscyamus (henbane) over the patient’s face.

Not least, by seeing to it that both his daughter and his granddaughter went into medicine, he became a pioneer in a different way. Though largely limited to obstetrics, these women began a tradition in the Muslim world that accepted females as medical doctors 700 years before Johns Hopkins University graduated the first American female physician.

Doctor and Philosopher

Born in Córdoba in 1126 and at one time a student of Ibn Zuhr, Abu ‘l-Walid Muhammad ibn Ahmed ibn Muhammad ibn Rushd was in many respects to the western caliphate what Ibn Sina was to the eastern one. Known in Europe as Averroës, he became known mainly for his works on philosophy. Ibn Rushd’s principal medical work, a slender volume called Kitab al-Kulliyat fi al-Tibb (General Rules of Medicine) became an important précis of medicine. Beginning with a brief anatomical survey of the human body, the book continues with sections on the functions of the various organs, systemic diseases, diet, drugs, poisons, baths and the role of exercise in maintaining health. The sections on surgery briefly cover the treatment of abscesses and the use of styptics, cauterization and ligatures. Perhaps most notably of all, he observed that smallpox “is a disease (that) attacks the patient only once”—the first known reference to acquired immunity.Doctor in Exile

Musa ibn Maymun (Latinized to Maimonides) was a Renaissance man before there was a Renaissance. He too was born in Córdoba, just 12 years after Ibn Rushd, to a family that had produced eight generations of scholars. The towering genius of his era, a Jew living in a Muslim world, his achievements covered law, philosophy and medicine. At an early age, he developed an interest in science and philosophy. In addition to reading the works of Muslim scholars, he also read those of the Greek philosophers made accessible through Arabic translations. His great work on Jewish law was written in Arabic using the Hebrew alphabet, and as a religious scholar he opposed the mingling of religion and medicine. He was the only intellectual of the Middle Ages who truly personified the confluence of four cultures: Greco-Roman, Arab, Jewish and European.When he was 10 years old, the less-than-tolerant Almohads conquered Córdoba. They offered the city’s Jews and Christians the choice of conversion to Islam, exile or death. Maimonides’s family chose exile, and they eventually settled near Cairo. When family tragedy reduced them to penury, he took up the practice of medicine.

Maimonides wrote 10 known medical works in Arabic. They describe, among much else, conditions including asthma, diabetes, hepatitis and pneumonia. They emphasize moderation and a healthy lifestyle. A doctor, he wrote, must be knowledgeable in many disciplines, treat the whole patient and not just the disease, heal both the body and the soul, and must himself be imbued with human and spiritual values, the foremost of which is compassion.

Throughout his medical works Maimonides often challenged what he called Galen’s “arrogant presumption” when it differed from his own experiences, leading to one of his key contributions: the idea that, in medicine, personal empirical experience trumps written authority. Nonetheless, his passion for order and learning led him to abridge the Roman physician’s massive literary output to a single book of key extracts that a physician could carry in his pocket. Though he was also a Talmudic rabbi, when it came to the understanding of disease, Maimonides was what today we would call a “natural scientist”—a strict empiricist—and he strove to clearly divorce medicine from religion. At a time when magic, superstition and astrology were all widespread in medical practice, his writings contain no references to these, nor to Talmudic medicine. That which is correct, he argued, is that which works.

One of Maimonides’s key contributions was the idea that, in medicine, personal empirical experience trumps wirtten authority.Maimonides taught that individuals should look after their own health by avoiding bad habits and seeking medical attention promptly when ill. “One’s attention,” he wrote, “should first focus on the maintenance of natural [body] warmth, before anything else. That which best insures this is [the performance of] moderate physical exercise, which is good both for the body and soul.” He then goes on to prescribe a daily regimen of walking for elderly patients, something with a distinctly modern ring to it. He also discusses the benefits of massage and touch as a means of stimulating the innate “heat” of the body, insofar as it rejuvenates the body naturally.

He recognized furthermore the medical benefits of positive thinking, leading to an early form of psychosomatic medicine. Whether certain amulets or trinkets were anathema to his rational world view was unimportant compared to the needs of the patient. If they made the patient feel better, he wrote, then having them present was best “lest the mind of the patient be too greatly disturbed.”

Secrets of the Heart

B y the time Ala al-Din Abu al-Hassan Ali ibn Abi-Hazm al-Qurashi al Dimashqi —far more easily known as Ibn al-Nafis—was born in 1213 in Damascus, the intellectual center of the Islamic world had become Ayyubid-ruled Cairo. While in his early 20′s, Ibn al-Nafis moved there and eventually became chief physician at the 8000-bed Al-Mansouri Hospital.At 29, he published the Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun Ibn Sina (Commentary on Anatomy in the Canon of Ibn Sina). The book described a number of his anatomical discoveries, including the earliest explanation of the pulmonary circulation of blood.

This modern gouache illustration depicting

Ibn al-Nafis is titled “Discovery of the ‘Small Circulation’”—the

movement of blood from the right ventricle of the heart to the lungs and

back to the left atrium. It was Ibn al-Nafis who first correctly

described the interaction of the heart and lungs in circulation and

oxygenation of blood.

Ibn al-Nafis also hinted at the existence of capillary circulation, arguing “there must be small communications or pores [manafidh] between the pulmonary artery and vein.” Though his hypothesis was limited to blood transit in the lungs, it would be confirmed for the entire body 400 years later when Marcello Malpighi described the action of capillaries. Moreover, after the 14th century, Ibn al-Nafis’s discovery was lost, and it was not until 1924, when Egyptian physician Muhyo al-Deen Altawi found a copy of the Commentary in Berlin’s Prussian State Library, that the full extent of Ibn al-Nafis’s work was understood—showing that it was he, and not William Harvey some four centuries later, who had discovered the circulatory system.

Unfortunately, Ibn al-Nafis’s fall into undeserved obscurity was not unique or even particularly unusual. Over those medieval centuries Muslim physicians by the tens of thousands, the great and the ordinary, lived and worked mostly outside centers of medical science. While they toiled, small groups of Christian and Jewish scholars also labored, filling for a coming era the roles of translators and disseminators that their Muslim predecessors had once filled for al-Ma’mun in Baghdad. Many were located along the porous, shifting, multicultural frontier with Spain where Toledo, Barcelona and Segovia offered them support; others gathered in the cities of France, Italy and Sicily that were touched by Islam. They too became cultural bridges, returning to a reawakening West both the intellectual foundations it had foregone nearly a millennium earlier and a rich legacy of discovery upon which today’s western medicine is founded.

The physicians who produced this legacy of discovery in the Muslim world devised techniques and further unraveled enduring mysteries of the human body and mind. They established hospitals and the professions of surgery, medicine and pharmacy, invented surgical instruments and applied empirical methods to test hypotheses. They separated religion from science and opened a door for women. Many of their precepts of personal health, diet and hygiene are common sense today. Perhaps most important of all, they re-taught European physicians that sickness is only a deviation from health, and that the role of medicine is to cure disease.

If any of this seems too easily self-evident to us, that is because progress turns yesterday’s discoveries into today’s everyday knowledge.

Friday, April 27, 2012

Iqbal - Obtiuary from 1938

Thursday, April 26, 2012

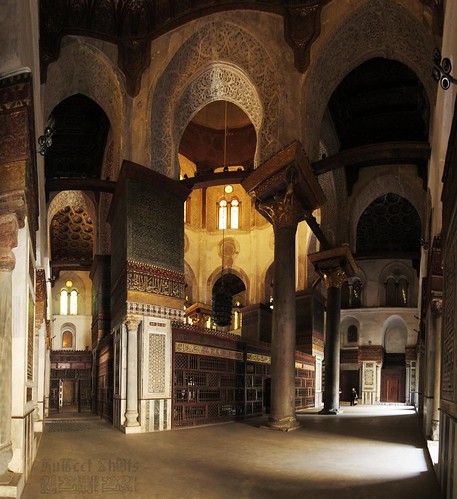

Qalawun complex in Cairo, Egypt

The Qalawun complex (Arabic: مجمع قلاون)

in Cairo, Egypt includes a madrasa, a hospital and a mausoleum. It was

built by the Sultan Al-Nasir Muhammad Ibn Qalawun in the 1280s; some

thirty surviving mosques were built during his time. The Qalawun Complex

was built over the ruins of the Fatimd Palace of Cairo, with several

halls in the Palace, it was sold to several people, where it was finally

bought by the Sultan Qalawun in 1283 AD. The structure resides right in

the heart of Cairo, in the Bayn al-Qasrayn, and has been a center for

important religious ceremonies and rituals of the Islamic faith for

years, stretching from the Mamluk dynasty through the Ottoman Empire.

Following images are hosted on Flickr and are being displayed here using Flickr’s own API.

The copyrights of each image are held by the respective photographer.

The copyrights of each image are held by the respective photographer.

© Fouad GM

Wednesday, April 25, 2012

Zaid Hamid -- UET Taxila - April 25th 2012

Alhamdolillah, we went to University of Engineering and Technology Taxila (UET) for a heart warming welcome and an emotional talk on our beloved Baba Iqbal. Listen to this carefully with your heart and soul, for it has come from our heart and soul, to present you the message, misison, duty and destiny which awaits you. This is a glad tiding for those who hear and see and a warning for those who are dead, deaf, dumb and blind. The destiny is written. It only searches the blessed to be part of it.

Tuesday, April 24, 2012

Science in Islam – the forgotten brilliance - By Markus Hattstein

Islamic science was in its prime during the European Middle Ages, between the 9th and the 13th centuries, particularly in the brilliant period of the Abbasid caliphate from the 9th century to the 11th.

|

| Socrates in discussion with his pupils, Seljuk manuscript, 13thcentury, Istanbul,Topkapi Palace Library |

The sciences of Islam, particularly the so- called exact or natural sciences in the widest sense, had from time immemorial taken as their unquestioned authorities (together with the religious sources of the Koran and the Hadiths) the writers of Greek antiquity, more particularly the philosophers Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, to whom every scientist referred in one way or another. Another authority was the physician Galen. Contrary to what is generally thought in the West, where the achievements of Arab and Persian science are seen as consisting almost exclusively in the preservation and transmission of the inheritance of classical antiquity, these scholars adopted an intellectually original and independent approach to the texts of antiquity; the Greek inheritance was not simply copied and read, but revised, brought into line with the requirements of Islamic culture (and religion), supplemented, and expanded.

|

| Treatise on alchemy, 18th century, London, British Library |

Philosophy and the caliph’s dream

Philosophy and all the other sciences received their first major boost under the scholarly Caliph al-Mamun (813-833) and his direct successors. Al-Mamun made the rationalistic faith of the Mutazilites the state religion, allowing philosophy to free itself from its subservience to theology. This encouraged an interest in the thinking of classical antiquity by announcing that a dignified old man had appeared to him in a dream, identified himself as Aristotle, and that he had expounded the nature of good on a basis of philosophical doctrine (rather than divine revelation).The first major philosopher of Islam was al-Kindi (c. 800-870), a descendant of a distinguished family, who took Platonic thinking as his point of departure, argued for the acceptance of causality, and also wrote over 200 works on subjects ranging from philosophy, medicine, mathematics, physics, chemistry, astronomy, and music. He was also politically influential as the tutor of princes at the court of Caliph al-Mutasim, where he introduced arithmetic using Indian numerals. Al-Farabi (c. 870-950), who bore the honorific title of “second teacher” (that is to say, second only to Aristotle) and was active at the court of the Hamdanids of Aleppo, combined Aristotelian thinking with neo-Platonism, and confidently stated that philosophy held the primacy over theology. In his book, The Model State, he sets out the pattern of an ethical and rational ideal state, ruled by a philosopher king who also has some of the characteristics of an Islamic prophet.One of the most important Islamic polymaths was Ibn Sina of Bukhara (c. 980-1037), known in the West as Avicenna. He worked to compile a detailed collection of all the knowledge of his time, wrote works on philosophy, astronomy, grammar, and poetry, and was regarded as one of the most outstanding physicians of his day. He also wrote a remarkable autobiography, and held important political offices at various princely courts. In his major work,The Book of the Cure (of the Soul), he combines metaphysics and medicine with logic, physics, and mathematics. His compendium of medicine was regarded as a standard work in Europe as well as the Islamic countries until the early modern period. Avicenna’s contemporary al-Biruni (973-1048), who came by adventurous ways to the court of the Ghaznavids Mahmud and Masud, and remained bound to it for the rest of his life in a curious love-hate relationship, proposed strong links between philosophy and astronomy in his book Gardens of Science. He accompanied Mahmud of Ghazna on Indian military campaigns, and wrote a cultural history of the Indian world.

|

| Elephant clock, al-Jazari, north Syrian manuscript, 13th cen¬tury, 33.8 x 22.5 cm, Istanbul.Topkapi Palace |

Philosophy in Islam reached its peak with Ibn Rushd (c. 1126-1198), who was also under the protection of the Almohads,and became known in the West as Averroes. As an uncompromising champion of Aristotle, he supported the idea of the eternal existence of the world and the cosmos, which had no beginning; in his doctrine they were created by God, but developed according to their own laws.The intuitive mind, Aristotle’s nous, was a purely intellectual entity to Averroes, operating on the souls of men from outside, and he therefore rejected ideas of the continued existence and immortality of individual souls. He came into violent conflict with Islamic orthodoxy, had to face many tribunals and hearings, and often survived only because he enjoyed the protection of the Almo- had rulers. The doctrine of the eternity of the world and its existence without beginning reached the West as “Latin Averroism” (its outstanding proponent was Siger of Brabant at the Sorbonne in Paris), and it was contested by the most important European thinker of the Middle Ages,Thomas Aquinas, who himself was strongly influenced by Aristotelianism of the kind proposed by Averroes. In the Islamic world, however, orthodox and dogmatic theology clearly gained the upper hand over philosophy.

The natural sciences: astronomy, physics, and medicine

Islamic science’s special interest in astronomy was derived from the traditions inherited from old oriental religious communities, such as the Parsees, and in particular the Sabaeans of ancient Mesopotamia, whose center was in the north of Iraq and who were largely absorbed by Islam in the 11th century. Under Hellenistic influence their original Babylonian cult of the heavenly bodies had given way to monotheism, but they still retained ancient oriental knowledge of the mathematical calculation of the course of the planets. Such calculations fascinated Islamic scientists because, under Greek influence, they developed a concept of the divine architect of the universe as a great mathematician and geometrician who kept everything in order by the operation of precisely calculable laws. Astronomy and astrology were closely connected in this system of thought,and the calculation of favorable conjunctions became a politically influential field of knowledge. All the important philosophers, and many rulers, took an interest in astronomy, calculated the courses of the stars and the dimensions of the earth, forecast the weather, and predicted the state of the water supply – calculations that served very practical purposes.

Calculation of solar and lunar eclipses, from: The Wonders of Creation, by al-Qazwini, Arabic manuscript, 14th century

|

| Anatomy of the Eye, by al-Mutadibih, Arabic manuscript, c. 1200, Cairo, National Library |

|

| Canon Medicinae of Avicenna (990-1037), Damascus, National Museum |

|

| Blood-letting machine, al-Jazari, north Syrian manuscript, 13th century, 33.5 x 22.5 cm, Istanbul,Topkapi Palace |

The compendia of Ibn Ishaq, Rhazes, Avicenna, and other scholars reached Europe by way of southern Italy and Andalusia. Avicenna’s Canon Medicinae, in particular, became a major textbook of Western medical schools. Arab physicians thus not only handed on the knowledge of classical antiquity, but were the direct forerunners of medical progress in Europe from the Renaissance.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)